Yesterday we got to take off our researcher hats and put on our outreach hats (we also traded our field clothes for some clean pants). Gail and I brought “Snooki”, the latest version of our robotic female grouse, down to Lander to participate in Teen Tech Week at the public library. Word had spread among the library staff; they were quite excited to get to meet the robot in person. Some of the kids were apprehensive, but most jumped right in to give the test drive. I had loaded some videos of the fembot and the grouse on my iPad so they could see how she looked in action.

With the exception of the wheels, the robot makes a pretty convincing sage-grouse. This version has the mechanics tucked inside a fiberglass shell that was poured over a grouse-specific taxidermy mold. Gail artfully arranged real grouse skins over this to complete the disguise. “Snooki” can turn in place using the wheels, the body can pivot down, the neck bend up and down, and the head can swivel back and forth. You can see a video of the fembot in action at the bottom of this post.

One of the common questions we get at this sort of event is “Is the robot just for fun? What do you do with it?” Let me take a moment to answer that.

In my recent post, I talked about how we use leks as a way to study sexual selection and mate choice. Most studies of lekking animals have looked at male traits that don’t vary much over the course of the breeding season. For example, in peafowl, biologists can look at which males have the longest tails or most tail eye-spots, and see if that might relate to patterns of mate choice. You could picture this as each male holding up a sign with his “score”, and females look around until they find the male with the highest score.

Anyone who’s watched animal courtship knows that males and females aren’t always politely assessing each other from a distance. Real courtship often involves complex decisions and interactions: deciding whom to approach, how quickly, reading signals or cues and responding accordingly. For a male to succeed in the mating game, the skills required to navigate the complex world of courtship can be as important as the physical traits he carries. Some of you may even have personal experience with this situation– meeting someone who is very attractive but who comes on a little too strong, for example.

Unfortunately we don’t know much about the importance of these “social skills” in non-humans because they can be hard to measure, especially in the wild. This is where the robot comes in. With a robotic female, we can control one side of the conversation. The fembot gives us two important tools for comparing males on the lek.

First, it presents all males with a standardized stimulus. In live courtships, females may approach the top guys much more closely and provide signals of interest, while other males are consistently given the cold shoulder. The robot lets us measure all the males on an even playing field.

Second, it allows us to experimentally control the conditions of courtship. In a previous experiment, we could look at how male sage-grouse responded to a very basic aspect of female behavior– how close or far away she is from a male. With the more advanced version of the robot that we debuted last year, we could send either “coy” or “interested” signals to the males. I’ll describe the plan for this year’s experiments when we get a little closer to conducting them.

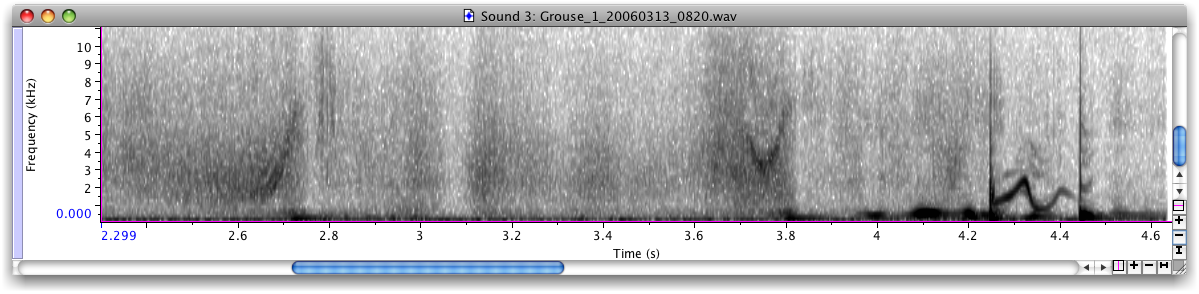

The robot also serves an important function as a target of courtship- one of the skills we are interested in is the male’s ability to aim his best signal at the female, and in a past iteration, the robot could record what a female would hear, rather than what a biologist can record from some arbitrary position on the lek.

There are several ways that biologists can manipulate an animal’s social environment (video playbacks in the lab, audio playbacks of bird song, etc), but the robot gives us a unique way to interact with animals in wild.